The Murakami of Our Times

- By Z.L. Nickels

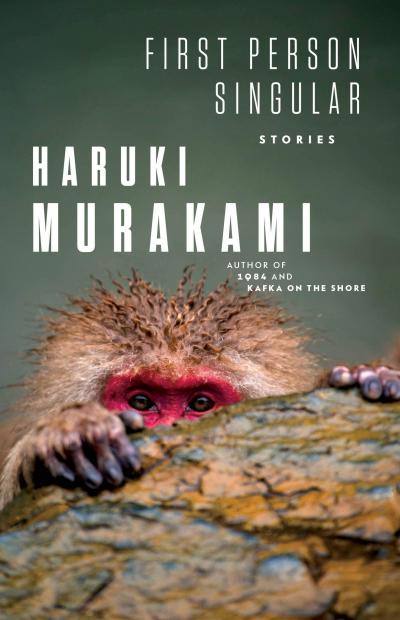

A Review of Haruki Murakami's First Person Singular. Transl. Philip Gabriel (Knopf, 2021)

The most significant story I have ever read was a Murakami story. I cannot say which one, only that it appears in the collection Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman. Consider this withholding a sacrament in the name of preservation: once you admit what is most important to you, you have committed an indelible act. I am not willing to surrender myself in this way. I have come too far (and taken far too long) to give up the ghost of the writer I wish to one day be. To relinquish this possibility would require my being fully convinced of myself. It would require being Haruki Murakami.

Not enough is said about Murakami the fabulist. This is, perhaps, an unavoidable byproduct of our fetishization of the novel, but Murakami has long embraced the short story. In his introduction to the English translation of the aforementioned collection, he asserts “if writing novels is like planting a forest, then writing short stories is more like planting a garden.” If this is true, it is especially so for Murakami. His stories are not unlike his novels; rather they aim at some other, more grounded truth. I do not know whether Murakami figures himself to be a realist, but as a short storyist, this label fits him best. Though he elevates the world in his stories (sometimes just above what we know, sometimes miles beyond it), it is always the world we inhabit. Always

His new collection, First Person Singular, has arrived at an interesting time in his career. The text bears a resemblance to his previous volume, Men Without Women, especially with regard to its length and underlying themes. His last novel, Killing Commendatore, was published four years ago and—save about 130 pages beginning with the chapter “Something Is About to Happen”—was largely underwhelming. At the moment, it appears as though Murakami is trapped in a similar position as many of his characters: he is caught in the in-between. He has not published a truly noteworthy work in the last decade, but neither his sales nor his reputation have suffered for it. For this reason, readers expecting a triumphant return to form will most likely view this collection as a disappointment.

But I cannot bring myself to be disappointed. Although Murakami’s status as an inimitable storyteller matters—and it does matter—the greater significance is his reemergence in our lives. The return I care most about is not the return to form but rather the return home. Murakami’s are the stories of my life. They are the stories of all our lives.

Four of the collection’s eight pieces were published prior to its release. I remember where I was for three of them. Each memory places me back in the orbit of a woman whom I am no longer seeing—a loss I continue to mourn. I read the first story, “Cream,” in her bed on a lazy afternoon in late January; “With the Beatles” came to my mailbox a year later, some twelve-hundred miles away, as I pondered whether I could spend the rest of my life with her; the final story, “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey,” was published a month after we decided we could no longer be together. In this last story, one which hinges on an act of testimony, I recognized the patent symmetry: the forlorn lover who steals the names of his beloveds; my beloved’s name that I alone carry.

I cannot read this collection without encountering these memories. In this way, it resembles my other experiences reading Murakami’s work; I suspect you might feel this way, also. It is what makes this collection difficult to analyze: when stories serve as touchstones for our lives, the traditional standards by which we judge them are often made immaterial by comparison. But traditional standards do have their use. Of these eight stories, only one can be called truly great and another awful—the rest lie on a spectrum between these extremes, depending on your own penchant for self-reflexive storytelling. We can locate this subjectivity by way of form: in this collection, the usual divide between reader and writer has been collapsed. We are not the only ones lost in these pages. Murakami is here, too.

With First Person Singular, the careful reader will naturally wonder whether its first-person narrator is the same narrator in every story or whether this character changes. Murakami has not chosen to give any of these narrators a name, save one: Haruki Murakami. In “The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection,” the author himself enters the text, writing about his favorite baseball team (which is, simultaneously, the narrator’s favorite baseball team) and the inspiration they provided for his fictious poetry collection. How are we to consider this decision? Even the inside jacket reflects this perplexity: “Occasionally, a narrator appears who may or may not be Murakami himself.”

Is this first-person narrator Haruki Murakami? And is this collection of short stories instead an assemblage of personal experiences papered over with the label fiction? In an interview with Petra Mayer, prior to First Person Singular’s release, Murakami had this to say:

“There's a long tradition in modern Japanese literature of the autobiographical, so-called ‘I-novel’. The idea that sincerity lies in honestly and openly writing about your life, making a kind of self-confession. I'm opposed to that idea and wanted to create my own 'first-personal singular' writing.”

In First Person Singular, Murakami makes an active attempt to obfuscate himself—therein, he believes, lies the sincerity. By retreating from the text, he opens a distance between himself and these stories. The resulting lack, or absence of the writer, is what ensures this is no confession. In fact, this distinction demands my apology: in recounting my own relationship to this text, I have not mirrored Murakami. I have simply provided a record; there can be no testimony when mere correctness is at stake. Murakami’s decision is a different one. It ensures his experiences cannot be fully accounted for.

That is to say, these stories can be convincingly understood as the stories of Murakami’s life. This is the lens through which First Person Singular ought to be read. In doing so, we exchange our traditional standards for conceptual awareness of how we might best interpret our own lives. This is the rewarding reading, the compelling reading. There are, of course, other reasons to read. If you are a reader who prioritizes those traditional standards, your enjoyment of this text will rest on whether you are a fan of Murakami and his work. If, on the other hand, this is your first encounter with Murakami’s stories, do not start with First Person Singular. Go back to his earlier works and experience him at his very best.

But if you enjoy Murakami, if you respect what he does, then this collection is worth your time. And if you love Murakami, as so many of us do, then may you rejoice in the strange delight of returning home to the first-person singular experiences that elevate our world.

Z. L. Nickels is an MFA candidate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. His writing has previously appeared with Crazyhorse, Rupture, Critical Flame, and Sinking City. He is currently working on his first novel, which examines the consequences of the death of the Great God Pan.