Autumn Journal on Autumn Journal: 15-16

- By Michael Thurston

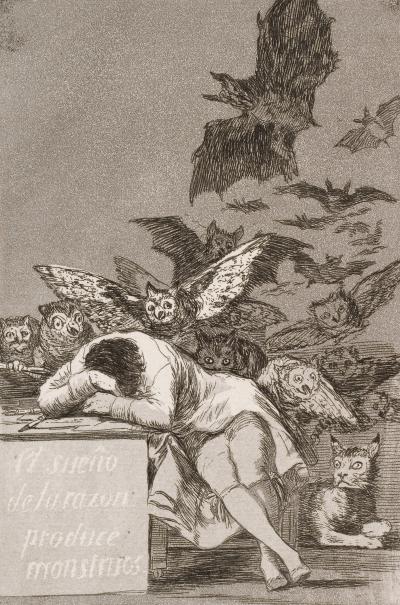

(Photo: Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes – The sleep of reason produces monsters (No. 43), from Los Caprichos)

“Nightmare leaves fatigue”

Exhausted by the stresses of pandemic, racial reckoning, a nail-biter of an election on which hinged the question of whether something like democracy continues or we slide on into authoritarianism, I fall asleep. Sleep comes easily at first; I’m out almost as soon as the lamplight dies. A couple of hours into the night, though, I am entering a dark house, sensing threatening presences, or I am captive at an execution, first as observer and then suddenly, seamlessly, as victim, or . . . you get the idea. I shout myself (and my spouse) awake and spend the next few hours still partly enmeshed in the nightmare’s atmosphere. My unconscious is an awful place to visit, and you really wouldn’t want to live there.

Is it any consolation that I’m not alone in this? Not really. But it’s reassuring that thinkers and artists I admire seem to be similarly plagued.

Back from Oxford, putting the stress of an election behind him even as international threats call him to action, MacNeice tries to relax, only to be plunged into nightmares:

O look who comes here. I cannot see their faces

Walking in file, slowly in file;

They have no shoes on their feet, the knobs of their ankles

Catch the moonlight as they pass the stile

And cross the moor among the skeletons of bog-oak

Following the track from the gallows back to the town;

Each has the end of a rope around his neck.

MacNeice’s nightmare has a nicely Eliotic ring to it (think of the shades crossing London Bridge in The Waste Land: “So many. I had not thought death had undone so many”). It has an Irish accent, too, with those bog-oak skeletons. Wondering at the familiarity of faces revealed when these figures remove their cowls, MacNeice interweaves the childhood terrors of a boy born in Ulster in 1907: Judas Iscariot, the mud-clotted dead of the Great War, the all-purpose “murderer on the nursery ceiling.” His unconscious is not such a great place either.

Confronting these figures, whether in sleep or in the waking nightmare of 1938, MacNeice desperately seeks and counsels distraction: “take no notice of them, out with the ukulele, / The saxophone and the dice.” As one would expect of a poet, his preferred distractions are literary. Section XV opens with “Shelley and jazz and lieder and love tunes,” and MacNeice trains his imagination not only on “a new Muse with stockings and suspenders / And a smile like a cat,” but also on “all the erotic poets of Rome and Ionia,” on stories whether old or new, and on “the songs of Harlem or Mitylene.” None of these work to dispel the ghostly figures, of course. The section ends with “they are still there.”

In the first section of Autumn Journal, MacNeice named and dismissed several literary genres (the “tired aubade and maudlin madrigal”) against which he positioned his own “autumnal palinode” (the song of unsaying). He’s up to something similar here. Lieder and love songs, Romantic poetry and Sapphic fragments, jazz and blues all fail to make the haunting figures vanish. Like drinking and erotic fantasy (to which MacNeice also turns), they are insufficient, lacking in the power necessary to awaken him (and us) from the nightmares of history. By so doing, and by continuing his own examination of the ghosts’ “blank faces,” MacNeice implies that the form adequate to the task is the one he has himself chosen: the journal. Or, as MacNeice puts it in a statement he sent to Faber in November for inclusion in the press’s spring catalog:

Not strictly a journal but giving the tenor of my intellectual & emotional experiences during that period.

It is about nearly everything which from first-hand experience I consider significant.

It is written in sections . . . as different parts of myself (e.g. the anarchist, the defeatist, the sensual man, the philosopher, the would-be-good-citizen) can be given their say in turn.

It contains rapportage, metaphysics, ethics, lyrical emotion, autobiography, nightmare.

To invoke Churchill (as MacNeice emphatically would not), the poem understands that when you find yourself walking through Hell the best thing to do is to keep going. The day-in and day-out attention to moments in their sequential passing enables MacNeice to confront head-on the specters that arise in his nightmare: “Sufficient to the moment is the moment.” Only by bringing to bear his journal’s peculiar blend of lyric and didactic poetry can the nightmare be navigated (rather than denied).

That navigation takes MacNeice, in section XVI, to his Irish roots. “Nightmare leaves fatigue,” he writes, envying those “men of action” who can kill when called upon “without being haunted.” But the enviable “intransigence of my own / Countrymen” quickly becomes not a laudable but, instead, a deplorable trait of the Irishness that he spends the entire section castigating, with the vitriol available only to the native. I know that rhetorical rage well, turning it often against the Texas within which I will admit only to having done time (I reject “Texan,” disclaim any association with the place, and return only under duress and reliant on the consolations of Shiner and Joe T. Garcia’s). Here’s a taste of MacNeice’s scathing take on his native island:

The land of scholars and saints:

Scholars and saints my eye, the land of ambush,

Purblind manifestoes, never-ending complaints,

The born martyr and the gallant ninny;

The grocer drunk with the drum,

The land-owner shot in his bed, the angry voices

Piercing the broken fanlight in the slum,

The shawled woman weeping at the garish altar.

Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus is not the only artist who realized the need, as a young man, for an Irish-born artist to find refuge in silence, exile, and cunning.

MacNeice’s boyhood church was St. Nicholas Cathedral, in the coastal town of Carrickfergus. My first trip to the cathedral was part of the MacNeice centenary conference held in Belfast in 2007. I sat with MacNeice’s biographer, Jon Stallworthy, during the bus ride from Queen’s University to Carrickfergus, chatting as much about rugby (Stallworthy and MacNeice both loved the game) as about poetry. We visited MacNeice’s grave (beside which Derek Mahon and Seamus Heaney and others read or quoted poems), we walked on the quais (where William III landed on his way to defeat the Stuart rebellion at the Battle of the Boyne, a victory still celebrated by Northern Irish Protestant groups during the infamous “marching season” around July 12, and where the effigy of a red-coated English soldier aims his rifle from atop the castle wall, and where there are more Union Jacks per capita than perhaps in any other neighborhood in Northern Ireland), and we spent an hour at St. Nicholas (where Heaney read again, brilliantly, movingly; God, I miss Seamus Heaney). I am quite fond of Carrickfergus. I’ve taken groups of students there to analyze the way power saturates the built environment (and to eat ice cream), and I’ve sung folk songs along with the castle guides. But the conference’s tour and talks felt wrong at the time because both aimed to draft MacNeice into precisely the identity (Irish Protestant, loyal to the British crown) that he so furiously denies in his poetry. Though he rounds out his screed by quoting Catullus—Odi, atque, amo—(“I love and I hate”), it’s really only the odi that comes through:

A city built on mud;

A culture built upon profit;

Free speech nipped in the bud,

The minority always guilty.

Why should I want to go back

To you, Ireland, my Ireland?

The blots on the pager are so black

That they cannot be covered with shamrock.

I hate your grandiose airs,

Your sob-stuff, your laugh and your swagger,

Your assumption that everyone cares

Who is king of your castle.

Ouch.

Digging into his identity in this critical way enables MacNeice to move on from his nightmare and to return to the preoccupations we have encountered in earlier sections. Sometimes, it is only by venting the odi that the amo can really be engaged.

Read Parts 17-18 here

Michael Thurston is the Provost and Dean of the Faculty, and Helen Means Professor of English Language and Literature at Smith College.