The Offending Classic

- By Deborah Jowitt

Sex and Death

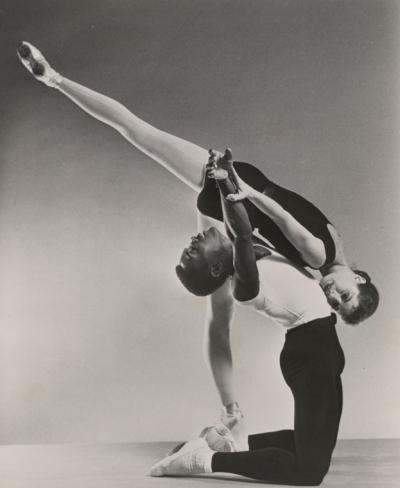

Photo: Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in Agon (1957) by George Balanchine. Photo by Martha Swope ©The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Several nineteenth-century story ballets that have survived the passage of time have similar scenarios. In Giselle (1841), a nobleman groomed to marry a woman he doesn’t much care for falls in love with a peasant girl with a weak heart. When death transforms her into a Wili, he becomes in thrall to her. This frail spirit, against her wishes, has been commanded by the Queen of the Wilis to dance him to death. Instead, she saves him and returns to her grave; he is overcome with grief.

In La Bayadère (1877), Solor’s bride-to-be, Gamzatti, sees to it that Nikiya, the temple dancer with whom he is smitten, is poisoned by a venomous snake. In an Act IV dream fueled by opium, Solor sees Nikiya dancing amid the bevy of white-tutued, supernatural spirits who populate Act IV, “The Kingdom of the Shades.” He falls in love again. And the gods, avenging Nikiya’s murder on the day of Solor and Gamzatti’s wedding, destroy the temple and everyone in it. Amid the wreckage, the spirits of Solor and Nikiya mount together into heaven.

Swan Lake’s Prince Siegfried is also something of a handsome, if principled, dimwit. In the ballet by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov (1895), he falls in love with Odette, the Swan Queen while he and his friends are hunting swans in the woods; though girls in an enchanted castle at night, by day they’re out in feathered disguise (don’t ask). In the end, Siegfried mistakenly vows eternal love to Odile, the sorcerer’s daughter, disguised as Odette (although wearing black). Death is inevitable. Odette throws herself into the lake, and Siegfried follows her into watery oblivion and transfiguration.

Secondary in all three works are the women who had been looking forward to their weddings. No one was raped in these ballets; the subject was taboo back then. But the female spirits were meant to thrill audiences by their beauty and tantalizing lack of physical urges.

What is easy to forget is the dichotomy between these ethereal, forgiving heroines of the nineteenth century and the extraordinary discipline and strength it took for dancers to create the image of fragility. This is especially notable with Marie Taglioni, the first Sylphide. Not only did she have to rise, however briefly, onto the tips of her toes, she did so in slippers hardened only with a bit of stiffening. To prepare her for the stamina her roles required, her father, choreographer Filippo Taglioni, insisted on a regimen of two private, two-hour-long classes every day, each focusing on a different aspect of ballet technique and the difficult task of maintaining a position for a hundred counts. She fainted a lot.

Today, there are other disparities between what we are supposed to see when watching a ballet and what is actually visible. This is particularly striking when a ballet has a plot. And only recently have writers pointed out the strangely aesthetic impact of stylized rapes, as in Kenneth MacMillan’s The Judas Tree (1992), in which the heroine is set upon by a group of men, and Manon (1974), in which the heroine is assaulted by her jailer in the penal colony to which she has been exiled. Such scenes are so pleasingly structured that violence is muted.

Sometimes, of course, a choreographer has an idea best expressed through a fantasy image. In Alexei Ratmansky’s 2017 Odessa for the New York City Ballet, six men carry Sterling Hyltin, carefully molding her into a relationship with Joaquin De Luz, often manipulating him too. Even though the sequence has a structure that could hint at group-instigated rape, its tenderness transforms it into a dream of love that might never occur.

Ballet dancers today can deliver super-virtuosity, sometimes in tune with a plot. Odile’s thirty-two fouettés are meant to suggest a weapon to ensnare Siegfried (sometimes you can hear knowledgeable spectators counting under their breath). Today’s expert dancers can make a triple pirouette reveal triumph or dizziness, rather than just tossing the audience an applause inciter. A long balance on one pointe can suggest maintaining equilibrium on a turning earth. It can also be presented as a show-off moment. I once labeled a supported turn the “Adieu Pirouette”; Romeo, urged by Juliet to rush away before dawn breaks, returns to spin her one more time. A multiple pirouette, alas, may require a preparatory plié, usually with feet planted apart in fourth position.

I’m fascinated by the differences that grew, in the recent past, between what we spectators felt and what we actually saw as dancers began to cultivate limberness unheard of in earlier centuries. A nineteenth-century dancer extended one leg no higher than her hip. A twenty-first-century dancer can lift her leg to form a 180-degree angle with her standing leg—maybe even more. If she’s wearing a short “classical” tutu, or one even shorter, what do we see? Her crotch. Is that really how you want to appear at the ball, Cinderella? Suppose, wearing such a tutu, the choreography has her sitting on her partner’s shoulder. And where is his head? All too often behind that net pancake. Most of the time, we in the audience think nothing of it. But those high extensions can alter the look of a ballet. The woman’s swept-high leg conceals her partner’s face; it may also take the attention off what the pair’s relationship means to them.

My own semi-blindness to such visions was shocked away years ago, during a summer session at Connecticut College’s American Dance Festival. Young, inexperienced students were among those occasionally offered screenings from the College’s film collections. During a contemporary duet—by John Butler, I think — they couldn’t restrain themselves. From the audience, you’d hear, “Ooh, that feels sooo good!” and “Come on, touch me there again!” Other, more knowledgeable viewers would shush them angrily. This was art. Art was. . . well, different.

In a dramatic ballet, a duet may create the image of an ecstatic union or a forced pairing, with only the characters’ motivations distinguishing between the two. These days we hardly notice where a male dancer needs to place his hands when lifting his partner. A pas de deux may also be about the difficult negotiations it requires. George Balanchine’s 1957 Agon contains an extraordinary one, created for Diana Adams and Arthur Mitchell. Not only was she white and he African American (unprecedented in ballets of the day), Igor Stravinsky’s foray into twelve-tone music provided its score. Carefully and thoughtfully, Mitchell assisted Adams into unusual, sometimes complex relationships with him. “Agon” means a contest, yet here the interaction is nuanced; her skills often allow him to help her accomplish what she initiated. The illusion of struggle is submerged by complicity. Watching film clips of the work, you see Adams begin a virtuosic move and achieve it with Mitchell’s help, but you also see him guessing its outcome as well as determining it.

I began by describing the plots of three nineteenth-century-ballets in which rape doesn’t figure but which do say a lot about onstage images of idealized, inviolate womanhood. That is, about men, their wives swaddled in corsets and hoopskirts, who desire chaste, disembodied beauties. Did these scenarios resonate, in particular, with upper- and middle-class men, able to avoid (and glad to escape) the mess and the squalling kids of nineteenth-century family life?

La Sylphide (1832) has an intriguing, slightly different message. James, a Scotsman, yearns to touch the ethereal sylph who is flirting with him and, with the help of a witch, he tries to render her human (in August Bournonville’s version for the Royal Danish Ballet, the besotted hero leaves a wonderfully warm family life to follow the sylphide, and the witch also has a yen for him). As he wraps the witch’s enchanted scarf about the elusive spirit, she begins to tremble, to weaken, and in a poignant theatrical moment, her little wings fall to the ground. She can no longer dance. Thanks to stage machinery, she travels up to sylph heaven, supported by a few of her companions. The witch triumphs. James collapses. Extra-marital lust is punished.

I am a dance historian as well as a critic. And although I’ve seen updated versions of nineteenth-century ballets, liked some and not liked others, I find myself interested in revivals that preserve as much of the original ballets as is reasonable. Why? Because they reflect the ideas, the prejudices, and the yearnings of people who existed long ago and, as such, they intrigue the historian in me. Of course, modern pointe shoes make a difference. Of course, blackface makeup—such as that worn by the children of Russia’s Bolshoi Ballet, who continue to play temple servants in the fictitious India of La Bayadère—can raise issues of racial insensitivity. And rape scenes. Were they inserted in more recent ballets to titillate? Or to depict virtuosic struggle?

No one that I know of thinks of repainting masterpieces to bring them into accord with current thinking, but I believe that old ballets, reconstructed by contemporary choreographers and performed by living dancers, are fair game for updating. The “original?” What was it? Would recreating it even be possible? Or desirable? Virtuosity would suffer. In the end, maybe what strikes a profoundly empathetic chord among spectators is the sight of human beings onstage doing what we secretly wish we too could do.

To watch a televised version of Agon’s pas de deux with Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams (the original cast), please click here.

Deborah Jowitt wrote for The Village Voice for forty-four years; her dance criticism now appears at ArtsJournal.com/DanceBeat. Her books include Jerome Robbins: His Life, His Theater, His Dance.

For other essays in this series:

Tanya Jayani Fernando, "Introduction: The Classic and the Offending Classic"

Deborah Jowitt, "Sex and Death"

Juan Ignacio Vallejos, "On the Intolerable in Dance"

Joellen A. Meglin, "Against Orthodoxies"

Nicole Duffy Robertson, "Classic Sin: Ballet, Sex, and Dancing Outside the Canon"

Mark Franko, "The Offending Classic"