Waging Peace in Memory

- By Jason A. Higgins

One hundred and one years since the end of the First World War, militarism still pervades American culture, and our collective amnesia about our own history puts the world at great risk. In 1973, the year American forces pulled out of Vietnam, Kurt Vonnegut wrote, about the end of WWI:

“It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind. Armistice Day has become Veterans’ Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not. So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.” (Breakfast of Champions 6)

A World War II veteran himself, Vonnegut saw clearly the erasure of peace as a celebrated ideal from American national identity. Two years later, Paul Fussell published The Great War and Modern Memory, arguing that war is necessarily ironic because it always lasts longer and destroys more lives than expected. The greatest irony is that each generation perpetually relearns the timeless truths about war. Time and again, waves of soldiers have marched to battle and confronted the “old lie”—that it is sweet and noble to die for one’s country. This forgetting does not occur naturally; it is by design. The public education system omits, sanitizes, or propagandizes the history of American wars. In my own case, I did not study the war in Vietnam until graduate school.

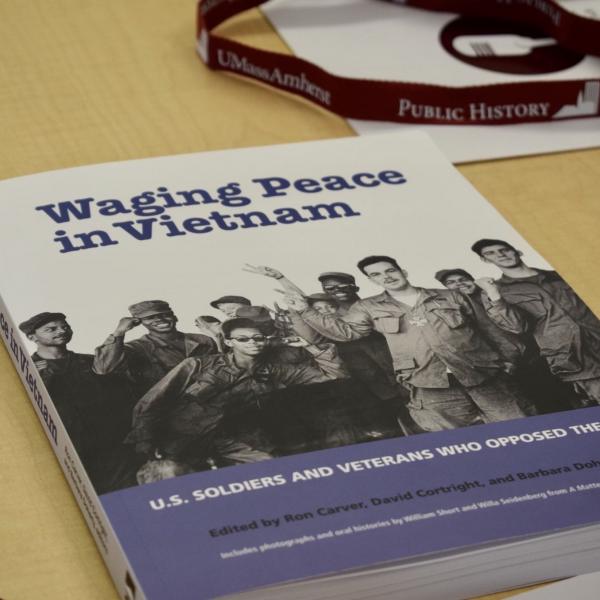

An exhibit currently touring U.S. college campuses, Waging Peace in Vietnam, helps to correct the misremembering of the war in Vietnam. It reinserts the voices of veterans against the war and documents the most powerful and most diverse grassroots antiwar movement in U.S. history. Told from the perspective of American soldiers and veterans who opposed the war, both the exhibit and the book which accompanies it ask us to recalculate who counts as a war hero and to reconsider our understanding of patriotism. Both argue explicitly that veterans served as powerful agents of peace and significant factors in the U.S. withdrawal of troops in Vietnam. This history contradicts one of the most pervasive myths and false dichotomies about the war—that peace activists and Vietnam veterans were in opposition. In fact, veterans and GIs led the peace movement, and their testimonies provide the most insightful sources from which we may learn from the past and mobilize young people for the challenges of the twenty-first century.

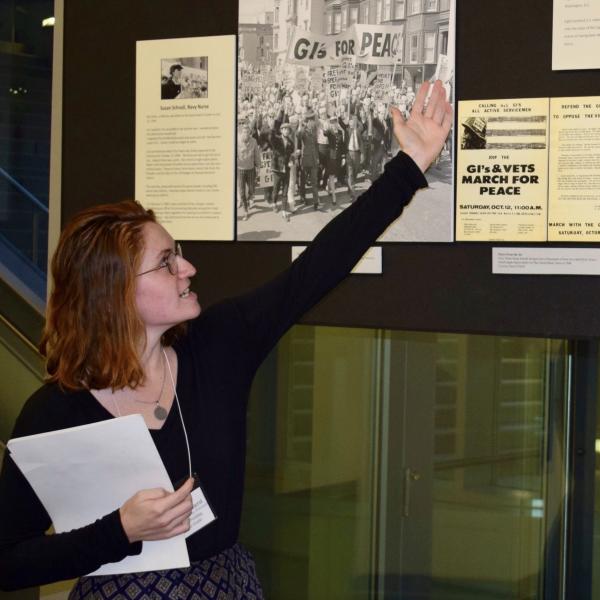

During three weeks, from September 23-October 11, the Waging Peace in Vietnam exhibit was at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and undergraduate students gave public history tours. A class I designed—History/Comp Lit 397Q: Waging Peace in Vietnam—provided a rare opportunity for students to experience and actively respond to this history. This public history course trained undergraduates to create and offer unique guided tours of the Waging Peace exhibit while it was in Amherst. Based primarily on the Waging Peace in Vietnam book, co-edited by Ron Carver, David Cortright, and Barbara Doherty, students identified significant themes and selected powerful stories that resonated with them on a personal level. As the instructor, I provided guidelines and an outline from which students added their own creativity and innovations. Students quickly took the initiative, and their involvement enhanced visitors’ experiences. During the first day of its opening, students practiced tours in small groups of three and worked together to tell a coherent narrative. On that occasion, I also modeled my own tour to the students; this example helped them weave historical context into their narratives. After receiving constructive feedback, students opened tours to the public during the following evenings. Before the book launch on Friday September 27, Ron Carver—the exhibit’s primary curator and a lifelong peace activist—also met with the students and gave us a tour. During the weeks that followed, students continued to develop and improve their tours, based on their experiences and audience interactions.

Over 240 students attended scheduled class tours, and hundreds more must have interacted with the exhibit less formally, given that it was displayed in an area of high student traffic. Undergraduate tour guides educated a range of audiences, from their friends and classmates to local Vietnam veterans and peace activists interested in the events. Students gave tours to large groups of over twenty, as well as more personalized tours with individuals. Smaller tours often turned into deep and meaningful conversations. The students helped make the exhibit a great success because they proactively recruited their friends, attracted peers by their passion, and bridged generational divides with their ability to relate past events to the present. There is a lesson to be learned here: if activists and educators want to enable young people and channel their energy into movement, we must let them lead.

“This course gave me the opportunity to teach and learn at the same time,”—undoubtedly a rare opportunity for an aspiring teacher, like Alec Bohlman, a senior political science major. Students were given two weeks to read Waging Peace in Vietnam and design their tours. Each student created tours by identifying major themes from the book, selecting stories that resonated most with them, and apprehending their significance. “My previous conceptions of the war were shattered,” admits Alec. While some tour guides had already taken History Professor Christian Appy’s “American War in Vietnam” class, several others had no previous knowledge of the war. One student was reluctant in the beginning, believing that any true public historian needed to be the ultimate authority on the subject matter. “I soon began to realize my idea of public history tours was inaccurate,” senior history major Hailey Morales comments. “A tour isn’t a lecture with the aid of historical materials; they are narratives, based on recollections of a moment in history.” Hailey learned to tell stories that could represent the most important themes in the exhibit. “Facts were obviously necessary,” she said, “but they didn’t need to be tediously listed. That way it feels less like an information dump and more like a conversation.”

Students were able to relate to their peers by telling engaging stories that were relevant to their lives. Caroline O’Neill, a senior political science major, says that she wanted to be a better tour guide than those she had previously experienced. When designing her tour, she reflected on “what to avoid when giving tours.” “I called upon past experiences on public history tours in which I was interested in the subject matter, yet still bored.” Caroline decided to tell stories that “would quickly encapsulate the most gripping and important aspects of the American War in Vietnam and the dissent and resistance to it.” She first invited her close friends to visit during her first tour. She quickly became a confident and articulate tour guide; she even offered a tour to a local news reporter. Later, Caroline invited a couple from the Amherst senior center, where she volunteers. “They were both involved in resistance movements and actually knew some of the veterans highlighted in Waging Peace in Vietnam.” The experience was meaningful because she realized that so many people in her life have been directly and indirectly impacted by the Vietnam War. History became personal.

The exhibit first asks us to consider who is most justified in opposing war. On a tour, one audience member responded: “The obvious answer is that veterans have more of a right to oppose war since they fought it.” I quickly added, “we all should have the right to oppose war.” As one veteran, Skip Delano, put it, “Since I had been in Vietnam, I had every right to comment on it” (Waging Peace 22). Although it was illegal to participate in political activities on active duty or in uniform, soldiers organized and dissented, regardless of the consequences. The public, however, must not rely on veterans alone to oppose our nation’s wars: citizens have a responsibility to make informed choices when electing their representatives, to hold policymakers accountable, and to honor veterans by acknowledging their experiences.

In 1965, at the beginning of the American war, a generation of soldiers believed they were fighting in Vietnam to stop the spread of Communism and to defend the freedom of South Vietnamese people. In country, soldiers experienced a traumatic rupture between their ideological motivations for fighting and their experiences of violence. Skip Delano argued that “for most soldiers, going to Vietnam and seeing the reality of the war. . . it was incomprehensible to most of us. I think most of us just immediately opposed that. . . on a gut level” (22).

Students were most surprised to learn that many of the GIs who resisted the war had volunteered to fight it. One story of a Green Beret, Donald Duncan, strikingly resonated with Alec Bohlman, one of the student tour guides. “Someone as hard-working and well-trained as Duncan coming out against the war was significant to me.” Alec found that Duncan’s voice had a strong impact on the audience. He quoted Duncan saying, “The whole thing was a lie. We weren’t preserving freedom in South Vietnam. There was no freedom to preserve. To voice opposition to the government meant jail or death. . . . It’s not democracy we brought to Vietnam—it’s anticommunism. This is the only choice the people in the village have. This is why most of them have embraced the Viet Cong” (10).

Many GIs and veterans responded to this shocking realization by writing about, documenting, and bearing witness to atrocities. Underground newspapers, created and circulated by American GIs, helped expose the crisis in legitimacy between the official narrative told by policy makers and the actual experiences of soldiers in Vietnam. These newspapers helped organize massive opposition to the war, and equally important, they provided historical documents, testimonies, and credible evidence of U.S. war crimes. An African American Vietnam veteran and peace activist, Lamont Steptoe claimed that “When I got back from Vietnam, I was very, very militant. But because I believed, and still do, that the pen is mightier than the sword and because I didn’t want to end up as a front-page lurid headline and break my mother’s heart—writing helped me turn from that violence” (33).

Tour guides focused on the agency of veterans who helped to document and disseminate evidence of war crimes. U.S. soldiers faced severe consequences for antiwar activities in the military. Maia Fudala, a history major, explains, “my tour emphasized the irony of the rhetoric behind U.S. official goals in Vietnam—to protect the freedom of South Vietnam from communist oppression,” while simultaneously imprisoning American soldiers for exercising free speech. Maia recounted the experiences of Terry Irvin, who was arrested for distributing copies of the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July. Irvin’s story is told in the book but not the exhibit; audiences were shocked to learn that American soldiers were arrested for sharing the Declaration of Independence. Maia says, “telling this particular part of history is very painful and complicated, yet imperative to remember and understand.” Despite these challenges, “the experience was life-changing.”

Amplifying the experiences of African Americans during her tours, Jade Spallina emphasized the relationship between the Civil Rights Movement and the peace movement. The oral history of Lamont Steptoe offered valuable insights: “I felt I was living this contradiction of being a black soldier in the land of another man of color and terrorizing him” (Waging Peace 32). Steptoe became deeply conflicted about his role in the war,” says Jade. “He felt uncomfortable about attacking and killing another racially marginalized group.” Like many Black veterans, Steptoe discovered a transnational racial solidarity with anticolonial liberation fighters.

Waging Peace in Vietnam also highlights the disparity between consequences for anti-war activities and the lack of accountability for American war crimes. In retelling these accounts, students grappled with notions such as heroism and patriotism. Annie Fielding, a senior history major, liked to talk about Vietnam veteran and author Tim O’Brien during her tours. Annie observes that, “Many of the students had read The Things They Carried, so it helped connect the new information presented in the tour with something they already knew. I mentioned the novel in connection with Mike Wong’s testimony about desertion in Waging Peace in Vietnam. Wong says, ‘People think we made these decisions lightly . . . I went to Canada with the assumption that I would be there for the rest of my life, that I would be an exile, a criminal, wanted by the FBI . . . and that I could never come home again” (Waging Peace 90). In a parallel story, “Tim O’Brien’s eponymous narrator decides to run away after receiving his draft notice. He makes it onto a boat in the middle of a lake near the Canadian border, and all he has to do is jump off the boat and swim to freedom. But he finds he cannot do it. “What it came down to, stupidly,” Tim says, “was a sense of shame. Hot, stupid shame. I did not want people to think badly of me. . . . I was ashamed of my conscience, ashamed to be doing the right thing. . . . And right then I submitted. I would go to the war—I would kill and maybe die—because I was embarrassed not to. . . . I was a coward.” (O’Brien 61). Annie’s analysis of these “two examples together help to challenge our assumptions about bravery and cowardice. This was one of the main themes I sought to weave into my tour,” She explains, “All of the men and women in the exhibit took great personal risks to oppose the war. Since it was illegal for soldiers to speak out, many of them risked arrest and imprisonment. Some even died. Many were dishonorably discharged, losing access to the G.I. Bill of Rights and disability benefits. It is not an easy thing to take a stand against the most powerful government and most powerful military in the world. Yet these men and women did. To me, that is a sign of true bravery.”

Susan Schnall, a Vietnam veteran and peace activist, spoke on a panel in Amherst on September 27, and students had the opportunity to meet her. Schnall told us that she opposed the war even before she enlisted in the Navy as a nurse. She joined because she wanted to help wounded soldiers; her own father died in Guam during WWII. In South Vietnam, she knew American pilots dropped leaflets on villages, warning the people to evacuate or risk death. In areas called “free fire zones,” the U.S. military evacuated entire populations of peasant farmers from their ancestral homes, relocating them into camps and cities like Saigon, where many young women were forced into sex work and other degrading occupations. This policy provided the U.S. official justification for indiscriminate killing of Vietnamese people. Susan Schnall had the brilliant and daring idea to use an airplane to drop antiwar leaflets on U.S. military bases. She also received a warning not to participate in any political demonstrations while active duty. In 1969, she was court-martialed for wearing her nurse’s uniform during a peaceful protest.

Audiences were shocked to learn about the experiences of soldiers incarcerated in U.S. military jails and prisons. Long Binh Jail (nicknamed LBJ) was a notorious military prison in Vietnam, a place where African Americans were disproportionately punished, and where racial violence was common. Back stateside, Fort Dix became infamous for its abuse of incarcerated soldiers. Toward the end of the war, discipline in the military had eroded to the point that the brass experimented with re-education tactics at Fort Dix. “Obedience to the Law is Freedom” was its Orwellian motto. During tours, Hailey Morales connected this part of the exhibit to a sign at Auschwitz bearing the German proverb, “Work Sets You Free.” As an oral historian and director of the Incarcerated Veterans Project, I interviewed an Army veteran who was imprisoned at Fort Dix. Glen Douglas refused orders to suppress riots in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and went AWOL [Absent Without Leave]. While imprisoned at Fort Dix, Douglas claims he was forced to walk a gauntlet of guards, during which he endured beatings and verbal abuse. He recalls clearly the sign that stated, “Obedience to the Law is Freedom.” I included Douglas’s oral history in my tours, and Amherst community members were stunned to learn that a local veteran had been imprisoned there. The Presidio Stockade in San Francisco was similarly notorious for its violence. One Vietnam veteran Richard Bunch experienced psychological issues while incarcerated; guards had denied him his medication. In 1968, a guard shot Bunch in the back as he walked away, killing him. In response to the murder, incarcerated soldiers engaged in non-violent civil disobedience, staging a sit-down protest and singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Both the book and exhibit rightly focus on the agency of veterans and the effectiveness of their opposition. Waging Peace in Vietnam also forces its audience to reckon with the capacity of U.S. soldiers to commit atrocities and the willingness of the chain of command to cover it up. As the instructor, it was my responsibility to help students navigate these difficult conversations and understand incidents such as the massacre at My Lai within its context.

Robert McNamara’s strategy for measuring victory in Vietnam relied on body counts. In practice, U.S. soldiers claimed any corpse as the enemy, and such practices led to systematically sanctioned atrocities. Drawing from other oral history collections, I often quoted from Larry Colburn, a helicopter gunner who helped stop the killings at My Lai. Witnesses to the ongoing slaughter, Colburn and helicopter pilot Hugh Thompson were prepared to shoot U.S. soldiers in order to save Vietnamese children. Colburn recalls, “The only thing I remember feeling then was these guys were out for revenge. They’d lost men to booby traps and snipers, and they were ready to engage. . . . They were going in to waste everything. They didn’t capture any weapons. They didn’t kill any draft age males. I’ve seen the list of dead and there were a hundred and twenty some humans under the age of five. . . . These were elders, mothers, children, and babies. Compare it to a little town in the United States. We’re at war with someone on our own soil. They come into a town and rape women, kill babies, kill everyone. How would we feel?” (Appy 348).

In the wake of My Lai, Lt. William Calley was the only U.S. soldier convicted of committing war crimes in Vietnam, yet he served as a scapegoat, a convenient figure head to take the blame for the disastrous military strategies that endorsed and rewarded the killing of innocent people. Ultimately, U.S. atrocities served to galvanize the resolve of the Vietnamese. For the murder of 504 Vietnamese civilians, William Calley was sentenced to life in prison but served only three years on house arrest. And yet, as Vietnam veteran Ron Haeberle said, “we are all guilty.” (Waging Peace 75). The killings at My Lai were symptomatic of genocidal tactics, including free fire zones and indiscriminate bombing, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated three million people. At the Winter Soldier Hearing in 1971, Vietnam veterans testified to witnessing widespread atrocities, rape and murder. No U.S. soldiers served time in prison for killing innocent people, but thousands of U.S. citizens were imprisoned for acts of resistance.

People are still dying from the consequences of the American war in Vietnam. Today unexploded ordnance litter the Vietnamese countryside, injuring and endangering the lives of people. Abigail Bedard, an English and History major, was stunned to realize that the U.S. dropped nearly twice the tonnage of bombs on South Vietnam compared to all its bombing during World War II. “More than 100,000 children and adults have been killed or injured since the fighting ended in 1975” (Waging Peace 169). After stating this fact, Abigail would then remind her audience that a total of 58,000 U.S. soldiers had been killed during the war. After decades of activism and veterans organizing, the VA now recognize the health effects of Agent Orange on U.S. veterans and many more are currently fighting for recognition of their service-connected disabilities from the war, but Vietnamese children are still being born with diseases related to the toxic and carcinogenic herbicide. The impacts of the war are both generational and intergenerational.

The U.S. government has never been held accountable for the millions of deaths of Vietnamese people or for the disastrous environmental impact of the war. However, Vietnam veterans themselves have engaged in various reparative projects, aimed toward healing the victims of the war, perhaps as a way to recover from their personal traumas. Lauren Soden-Bridger, an international exchange student, attests, “the audience seemed particularly interested in the stories of veterans and protestors who continued humanitarian work to aid Vietnamese survivors of the war.” For example, Army veteran Chuck Searcy founded Project RENEW, which has helped safely dispose of unexploded ordnance and provide medical assistance to survivors of bomb explosions.

In her conclusion, Abigail Bedard discussed the all-volunteer force and the civilian-military divide. She pointed out that veterans today are no longer drafted, but they join for a variety of reasons related to socio-economic class: lack of access to college, opportunities, and career possibilities. In 2008, two hundred veterans from the war in Iraq participated in a Winter Soldier Testimony. While none of the vets reported incidents as horrendous as My Lai, their accounts reveal pervasive problems in military culture which ultimately result in the radicalization of civilian populations under U.S. military occupation and eventually cause blowback against the U.S. itself. For example, Iraq Veterans Against the War reported a general disregard for the rules of engagement and widespread dehumanization of Iraqis, as well as accounts of sexual abuse and racism. U.S. soldiers detained innocent people, raided the homes of civilians, and performed degrading acts on prisoners of war. The American War in Iraq has displaced millions of people and created the destabilizing conditions under which ISIS rose to power in the area.

Many patriotic U.S. soldiers have served as agents of peace and powerful forces of resistance in the military. Public memory of the war has been distorted by right-wing propaganda since the 1980s, accounts that cast U.S. soldiers as the primary victims of the war. Vietnam veterans and protesters are often portrayed as enemies and groups mutually opposed to one another. However, as Waging Peace in Vietnam demonstrates, the antiwar movement was effectively led by GIs and vets who opposed the war, and it was their resistance that helped convince policymakers to withdraw from Vietnam. Both the book and exhibit show the necessity of “supporting the troops”—but not as an empty gesture. Instead, we must honor the experiences of soldiers and listen to the voices of veterans. If we did listen, Christian G. Appy writes, “we might find . . . that our nation’s military personnel well understood the contradictions between how our foreign policy is justified (always on the side of democracy, freedom, self-determination, and human rights) and its actual conduct and consequences” (Waging Peace 193).

Veterans in the twenty-first century have become tokenized and idealized as symbols of patriotism—not necessarily to “care for he who has borne the battle”—but to silence the dissent of the people and to quell criticism of U.S. foreign policy. Constructing the American Veteran as a symbol of our exceptional military strength comes at great costs to veterans themselves. Veterans with disabilities, survivors of trauma, women, LGBTQ, and veterans of color are further marginalized and erased from public memory. The disconnect between the civilian world and veterans of empire grows; less than one percent of the population serves in the military.

A vast network of over 800 military bases encompass the globe, and yet the citizens of the U.S. are increasingly isolated from their empire. The war in Afghanistan began before many of my students were born. Almost two decades since George W. Bush launched the Global War on Terror, the costs and consequences of maintaining the largest, most expensive, and most environmentally destructive military force in the history of the world go undebated in the mainstream media and mostly unrealized by the public. “The concept of informed patriotism is an important lesson for us in today’s political climate,” says Maia Fudala. Most of the students made clear connections between the antiwar movement and their current lives. Abigail Bedard writes, “the protest methods used during the American War in Vietnam can be implemented and updated to address global warming; if we are willing to face the consequences, then change can happen.”

Jason A. Higgins is a Ph.D. candidate in History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, writing a dissertation on the history of incarcerated veterans from the wars in Vietnam to Afghanistan. Since 2011, Jason has completed over 100 oral history interviews with military veterans. He is also the co-editor of a forthcoming collection of essays with the University of Massachusetts Press, Marginalized Veterans in American History.

The Waging Peace in Vietnam exhibit was designed and curated by Ron Carver. UMass Amherst faculty sponsors for the exhibit were Chris Appy, Jim Hicks, and Moira Inghilleri, and it was brought UMass with the help of the Department of History, the Program in Comparative Literature, the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, the Writing Program, Special Collections and University Archives, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts and the Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies.

Works Cited

Christian G. Appy, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides. New York: Viking Press, 2003.

Ron Carver, David Cortright, and Barbara Doherty, Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veteran Who Opposed the War. New York: New Village Press, 2019.

Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Breakfast of Champions. New York: Delacorte Press, 1973.