Massachusetts Reviews: The Son of Black Thursday

- By Joe Boisvere

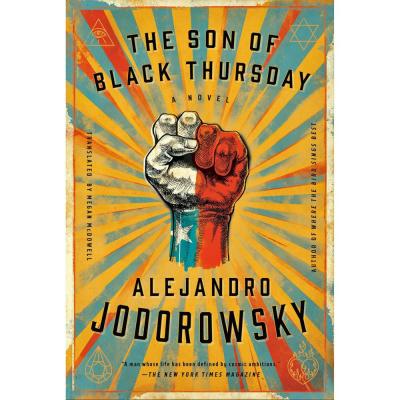

The Son of Black Thursday by Alejandro Jodorowsky, tanslated by. Megan McDowell, Restless Books

Alejandro Jodorowsky has been alive for nearly a century. For at least half of that time he has been a jarring creative presence in arthouse cinema, which is a difficult milieu within which to be jarring. His films such as The Holy Mountain and El Topo, as well as his unrealized vision for a massive adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune are the stuff of legend for the cineaste: violent, disturbing, sexually explicit, and in terms of narrative, difficult to access. A polemical figure, the filmmaker is as often hailed as a visionary as he is condemned as a misogynist and predator. The Son of Black Thursday (Restless Books, 224 pages) in this deft new translation by Megan McDowell, is a work which stands unapologetically washed in this light. It is challenging in terms of structure, character, and theme in ways befitting the story of the birth and early life of Jodorowsky, as told by himself seven decades later.

The author is our first-person narrator, but he is by no means the protagonist. Instead, he reports the fictionalized adventures of his parents, Chilean-born Ukrainian Jew Jaime and Sara Felicidad, beginning in the years before his birth and ending in his adolescence. While the novel draws the reader from the grotesque into the macabre, it owes its lineage more to the picaresque tradition than the gothic novel or even the avant-garde cinema of the 1970s, Jodorowsky’s most well-known artistic register. In fact, besides the Bible, the only texts that are mentioned within the story’s diegesis are stories of adventure and chivalry. The novel is composed in this mode. It is episodic although crafted along a thread as Alejandrito’s parents are thrown from one unexpected adventure to the next, from their humble port town of Tocopilla to desert copper mines, to their decade-long separation and eventual reconnection in Santiago. These seemingly aleatory, even hallucinatory episodes become links in a chain which is cast solely to be undone in the book’s final chapters as Jaime must atone for his spiritual misdeeds throughout the story under the instruction of a spectral rabbi who inhabits the body of his young son.

This picaresque world is peopled with the trademark apparitions of Jodorowsky’s silver screen works. One of the first we meet is Rubí Grugenstein, nubile heiress to a brutal strip mining operation in the Chilean desert who, moved by the treatment of the workers by the company’s management and private police, chooses one of the miners to father a Chilean/American who will stand in for a new classless race. She forsakes all clothing as she spends months working at a solid metal ingot, trying to mold it with her bare hands. Jodorowsky does not mince words when relating her effect upon the male characters, as when Jaime bemoans his uncontrollable erection that is, “like a bar of red-hot iron that wanted not only to possess, but also to leave a mark, so that the woman would have his signature on her flesh and be always his, and no one else’s.” The novel is filled with such musings, and the characters are often grotesque in appearance or demeanor. There are turpentine-chugging drunks, a lusty hunchback, many, many, exceedingly brutal police officers, and farcical political factions. With Jaime away on a mission to assassinate the country’s dictatorial leader, Sara Felicidad becomes the darling of local communists who enlist her to unite them with the Trotskyists against the fascists. When she fails, the communist leader implores her to sign a membership card to become an official party constituent; the moment she does so, he tears the card to shreds, warning her that later on the Trotskyists will be by to machine-gun her home in further retribution for her failure.

Inevitably the interactions of Jaime or Sara Felicidad begin with the filthy, the abject, and the unmentionable, contain an element of the sexually transgressive, and end in the realm of the cosmic. The main characters lack human-like complexity and instead are built upon literary tropes, single-minded devotion to various goals, or singular, dominating personal traits, making them allegorical more than realistic. Jaime’s development as a protagonist from practical and macho to spiritual and sensitive is only possible by dint of his unwavering simplicity. Sara Felicidad in particular is a stand-in for the cosmic mother who nurtures the son and lover in ways which often overlap. She regularly castigates young Alejandrito for looking down upon the city’s vagrants, whom Jodorowsky goes to great lengths to humanize and validate, drawing these caricatures in from the margins of society and rendering them tenderly and sincerely; these minor characters are often more sophisticated in terms of their desires and perspectives than those around which the novel revolves. From this tone of piety come ruminations on justice, charity, autonomy, and acceptance that weave through the taboos that are peppered throughout the novel’s adventures. The voice of the rabbi, a holy soul who possessed Alejandro’s grandfather, father, and then himself, is the avatar of Jodorowsky’s idea of masculine holiness. The rabbi delegates the tasks of repentance to the newly returned Jaime, whose exploits have manifested in a paralysis of his hands. He also coaches Alejandrito from the age of seven in a sort of humanist folk theology which comes laced with quotations from the book of psalms. Both Alejandrito and Jaime are relegated to the role of naïve initiate. The young boy Alejandrito is friendless and spends his youth attached to his mother or locked in debate with the rabbi. Jaime is itinerant and barrels through the novel on a quest to murder a dictatorial colonel but is haplessly stymied at every turn, his good nature getting the better of him or a twist of fate sending him ricocheting around Chile, at times paralyzed or without his memory, reminiscent of Voltaire’s Candide or Gracián’s Andrenio.

The Son of Black Thursday is not for the faint of heart. Its themes and its author’s frank disregard for decorum and willingness to inflame and transgress sound throughout the text like the siren signaling shift changes at a copper mine. The translation renders a narrative voice that is direct and matter of fact even as the dialogue maintains color and nuance. This rendering allows the text to read like a series of scenes from a classic Jodorowsky film which are strung together around the errancy of the author’s mythologized parents. The novel is for those who are looking for either a postmodern take on the picaresque tale or the die-hard Jodorowsky fan: while the premise and tempo of the story are interesting and the text is at times quite poetic, the book’s episodic structure betrays a lack of novelistic sophistication in favor of indulgent literary imagery.