Massachusetts Reviews: Spectra

- By Robert Manaster

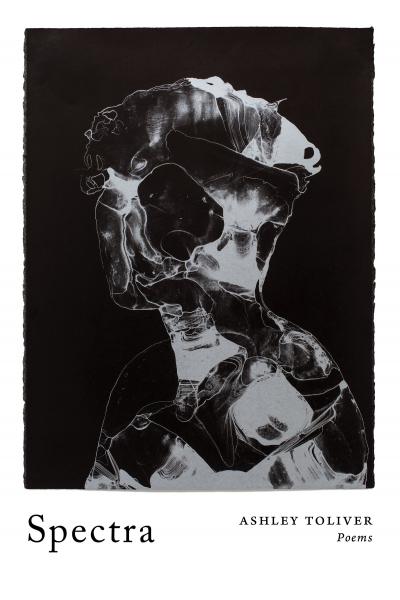

Spectra: Poems by Ashley Toliver (Coffee House Press, 2019)

"Kinesis," the first poem in Ashley Toliver's powerful first book Spectra, frames the collection's primary strength: that of movement through trauma and the emotionally dark places in the female self, where one can be "plumbing / a violent kinesis. "This movement takes place via Toliver's poetic form and her charged poetic language. While near the collection's beginning, the female speaker's husband in "Long Division" is waiting for "a woman / to crawl out of / herself," by the collection's last poem, the speaker sees herself "in the last pew / of the lit horizon / in the wide-open field of the now." The forces that constrain and inspire the speaker's growth shift from her male partner's physical and emotional abuse in the compressed first section to her struggle with optic nerve cancer throughout the spatial middle section to the last section's "ripening" of the "blue tilt" at dusk where there's "no northern limit / in the capacity for awe."

Most of the poems in the first section, "Housekeeping," compress shards of lines into flash-prose poems, which take the same titles as the section's. While the title implies a uniform kind of keeping order and keeping track, which traditionally has been a domestic role for the American female, something difficult in these poems and barely navigable is going on, which surfaces then plumbs underneath, as here:

Dear Night possessor: your funeral barge rocked tight in the fisting water makes small winter melodies. The light ends a pattern we learned to stupefy by motion or admitting away. A statutory list puts blame on the last hour. You move as I move, whistling measures in salt grass, patient and guarded processions. At night, the line is a current to wade through: older names sifting past the flotsam, the water rising up to here.

Threats seem everywhere. There's always movement and tension of contained violence in the "fisting water" and elsewhere. This section is one of emotional intonations, mostly violent — a male abusing his female partner. The flash-prose poem form works well in its attempt to contain the speaker's emotional ballast. Its strengths lie in the charged language within nonlinear movement and especially in the tension between a surface "housekeeping" and emotional undercurrents.

There are strong, effective juxtapositions and ambiguities. An early poem "Housekeeping" in this section, for instance, begins: "A pocketed wailing beneath clean clothes is what. Making hair pulled taut into windows just the same." While "wailing" is hidden, the speaker explicitly reveals it. Things appear normal like "clean clothes" though "wailing" suggests otherwise. The speaker seems to be both speaking publicly to a reader and as if privately in an edged-with-pain code, which skipped words suggest. The "making hair pulled taut into windows just the same" is also powerful in its ambiguous, absent subject. Its tension is one of presentation (speaker making hair taut) and one of violence (speaker's "you" pulling hair).

In navigating through her cancer of the optic nerve throughout the second section, "Ideal Machine," which seems to be one poem, Toliver's speaker releases the pressure of the first section's compression by using a spatially open form:

with the body

she coaxes to peel from itself like magic

the intent to un-suture layer after layer

raking free

vulgar eye waxed blind to wonder

As the speaker undergoes preop, surgery, and recovery, the poetic movement is freeing and precise, as here: "the bone first anatomical then moth / then / Lepidoptera." The bone as functional anchor metamorphosizes into the lepidoptera — butterfly, moth, etc. — as a creative force in its colors, patterns, and movements. The bone to which the speaker refers is the sphenoid bone, which forms the back of the eye socket and looks like a butterfly. Toliver uses this image to intersperse this section with five visual pieces, which reflect this poetic movement, ranging from a diagram of the sphenoid bone to a sphinx moth to a magnetic resonance of the brain. Just as bone is transformed into lepidoptera so does the female speaker transform.

A few lines later, the speaker poetically bursts out, "stamen eye you metastasize." In the phrase "stamen eye," beauty/nature/reproduction in "stamen" pairs with the physical body's "eye" along with the pun on self ("I"). The forces within her are at once beautiful and creative, yet there are also threats. In "metastasize" the speaker verbalizes the dangers in this compressed phrase. "Stamen," a flower's male sexual organ, links to her abuser in the first section, and "eye" links to her optic nerve cancer in this section. The speaker becomes more herself in this literal and metaphorical dark as she works to come to terms with her cancer (and abuse), to incorporate its being and transform its energy into something more life affirming in her.

This metastasizing growth becomes a birth, " dear Lepidoptera / womb of the mind / inside you our son splays to life." While there's danger (cancer of optic nerve and an abusive male partner), there's a butterfly and son who seem to dissolve this danger by carrying on intimate, creative forces within her. She frames this section via the intimate address "Dear," repeatedly addressing lepidoptera and her daughter. She also addresses her optic nerve, son, surgeon, and tiny icicle (part of her cancer). This varied addressing creates an emotional intimacy, which in the first section is compressed and fractured.

In the last section, "Spectra," which is the last poem, the speaker immerses herself in "mimosa blossoms / radial mimetic of energy stamened into sky" and confers "we can make an eden out of even this." Stamen is transformed from eye (and "I") to mimosa's blossom to sky. It's an opening up. At the same time, there's revival in energy and compression, "why is the dark / so dazzling." There is renewal in this language, a bit more heft than the last, more-opened section yet not as densely squeezed as the first. There's more space to breathe, more for the speaker to take in: not too quick, not slow; not compressed, not too spatial. There is seeing and a language of being, both of which are bursting forth from "somersaults of fragrance and rot"—such powerful language alive with tension yet grounding the speaker.

At the profound end of the first section in "Standing on the Lawn Outside Your House with a Match and a Gallon of Gasoline," the speaker has courage to plumb uncertainly into the depths of self:

I still don't know what kind of woman

I am. But as the flame nears the fingers

that trust the match, as close as the skin

can stand it to singe, I call this the nerve

to find out—

By the end of this worthwhile collection, Toliver's speaker seems to have found this self and the positive forces within her at the present moment. There is magic in life "ripening / magic on top of / magic on top of / magic." There's joy in being alive for the next "kind thing."

Robert Manaster has published poetry book reviews in such publications as Rattle, Jacket2, Colorado Review, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, and Rain Taxi. His co-translation of Ortsion Bartana's poem "In Every Room a Different Journey" appeared in last summer's issue. His own poetry has appeared in numerous journals including Rosebud, Birmingham Poetry Review, Maine Review, Image, and Spillway.