Favorite Things: Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring

- By Nicole Duffy Robertson

When Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes presented The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps) at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on May 29, 1913, an unsuspecting Belle Époque audience was shocked. The premiere of Sacre is the stuff of legend, with audiences hissing and screaming obscenities, and the dancers stunned and unable to hear Igor Stravinsky’s music, prompting choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky to run from the house to the wings, yelling the counts for them to be able to continue the dance. The controversial ballet was performed only nine times (including the dress rehearsal) and then dropped from the repertory for most of the twentieth century.

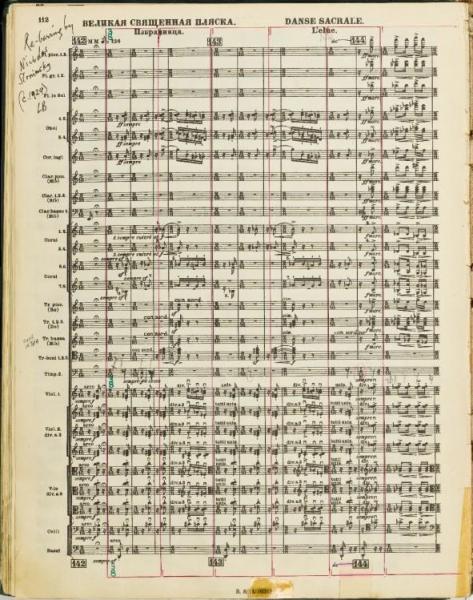

After years of dwelling in the dance world imagination, where it reached almost mythical proportions, Robert Joffrey put the legend back on the stage. Over ten years in the making, researcher Millicent Hodson staged Sacre for the Joffrey Ballet, igniting yet another controversy – about the viability of recovering a dance past from only the slightest fragments: oral history, photos, memoirs, an annotated score. Over the years, the Joffrey programs went from announcing “Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring” to “The Rite of Spring, after Nijinsky.” Nonetheless, this version continues to surpass the hundreds of attempts to choreograph Stravinsky’s music, and, although a century has passed, the ballet has not lost its strange, bewildering impact on audiences or the dancers whose bodies re-perform it.

Ballet dancing is a distinctly individual quest for perfection through a highly codified Western classical form, yet Sacre demands the opposite: dancing anonymously in baggy costumes, face paint, and wigs, arranged in assymetrical groupings, executing anticlassical movement – angular, turned-in, bent-kneed, flat-footed, loud, and violent. It was a shock to the original dancers, and it was no different for my generation. The ballet begins with “The Adoration of the Earth” – dancers arranged in several circular groups by gender (the youths, some with bearskins, some with beards; young maidens either in red or blue,) facing each other, hunched over or squatting, immobile and tense, like a huddle before a football game. Our stillness during the first few notes of the lonely, melodious bassoon was like the calm before the storm: an enormous unleashing of physical exertion and communal ritual was about to begin. When a group of young men started pounding the floor with their feet, we all felt like we had just boarded a bullet train with no brakes [3:00]. As a maiden in blue, curled into a tiny ball on my knees, on the floor, I could feel the vibration of their pounding through the floorboards as I breathlessly counted every note, waiting to unleash my first move and join the violent fray, adding my own intense energy to the group. The other four women in my circle did the same; we felt like one, tight unit about to explode [5:25].

A brief and welcome reprieve is built into the first act, where the energy comes down a notch and we bend down to touch the earth many times, as if tilling the soil [7:58]. But soon the calm passes, and we begin the race again, running in a crowd like a group of marathon participants, first stomping loudly and then spinning in place [12:18]. Later, right after the Old Sage kisses the earth and the “sun comes out” [13:50], a favorite moment: “solos” where we jumped, shook, rolled on the floor, and convulsed in highly choreographed movement, but in place, all of us at once, while trumpets blared and cymbals crashed. There is no other moment in ballet quite like it: absolutely unbridled, wild yet structured chaos and freedom in movement [14:10].

The idea of staging an ancient Russian ritual came to Stravinsky “in a dream.” Far from their homeland – the Ballets Russes never performed in Russia – in the early years they created ballets steeped in nostalgia for a mythical Russian past. Nijinsky’s vision of Sacre is about community: the notion that the power of the group can bring about cosmic change. Although the climactic ending is danced by a single woman – the Chosen One, her individuality is completely subsumed under the weight of her mission. Her solo is not about her, but about the beauty of her selflessness [24:20]. She overcomes her fears and dances herself to death, accepting her destiny for the good of her people – a resonant theme in a world on the brink of catastrophic conflict, then and now.

It was uncomfortable and sometimes painful to dance Sacre with the intensity it required, especially during long rehearsal periods – there was no “marking” the steps: it was all or nothing. Executing the sharpness and angularity of the movement while keeping the counts to Stravinsky’s fiendishly difficult score kept us focused and on edge. But performing it was exhilarating: surrounded by that orchestral tsunami, compounded by the raging, whirling bodies of my fellow dancers, it felt like surfing on top of a huge wave: an absolute freedom that could turn into a disastrous tumble at any moment. There was a strange satisfaction that came with dancing Sacre: embarking on an epic journey together, we felt united by our survival of the process, the strangeness of our task, and our part in recreating history.

(Please click here to watch Nijinsky's Rite of Spring, as performed by the Joffrey Ballet.)

Nicole Duffy Robertson is the associate director of New York Dance Project and a repetiteur for the Gerald Arpino Foundation.