Something Solid and Unshakable

- By Clare Richards

"I slid my hand down and clasped the small pair of tweezers I’d placed in my pocket before leaving for work that morning. [...] A recent habit of mine. Big or small, holding a solid object put my mind at ease—as if its hardness was preparing me for something."

—from The Lake, by Kang Hwagil, translated by Clare Richards

Reading this section, each time I’m transported somewhere hostile. Walking down the wide street back to my old apartment in Seoul; in the heat my mask is like sandpaper and the bulging beads of sweat form patches on the fabric. The sun is not just hot, of course, it is bright, and I can see everything, all at once—every single flyer that has strayed from stacks randomly discarded instead of slotted in post-boxes, every mark, line and wrinkle on the face of every passerby, every fallen overripe persimmon, tomato-like as they ooze their contents onto the scorching concrete. Or perhaps it’s the assault of fifteen hand-dryers resounding in chorus beneath rows of lurid strip lights in London Victoria station. Maybe it’s the clawing of a label I forgot to unstitch from a new piece of clothing and it’s all I can think of. I slip my hand into my pocket, and tightly grasp whichever solid object I’ve placed there—a comb, lip gloss—anything as long as my fingers can stretch around it. I clutch so tight that my palm might merge with it. And so, if only temporarily, the sensory onslaught feels a little more bearable.

Throughout Kang Hwagil’s short story, “The Lake”—published in my translation in this winter’s issue of the Massachusetts Review—over and over, protagonist Jinyoung repeats this action of reaching down into her pocket and clasping the same pair of tweezers. Here, it is her attempt to allay a different kind of anxiety: the ubiquitous fear and self-doubt surrounding male violence, which looms and closes in like a dark cloud (this is also the central theme around which Kang builds tension and suspense in her Gothic thrillers). At the same time, it resonated so acutely with my experience of autistic anxiety: clutching onto something solid and unshakable in a world overwhelming and uncontrollable (the Intense World Theory, for instance, tells us that autistic people feel more, sense more, and perceive more). For an autistic person, the solid and unshakable may come in many forms: in something physical, like the grounding of a weighted blanket, in our carefully crafted routines and faithful adherence to them, or in the hyperfocus that comes when engaging with our special interests. These are the same very sensible and effective tools for regaining a sense of control and peace amidst overstimulation and overwhelm that are pathologized by researchers and clinicians alike as “ritualized behaviour” and “fixated interests.”

You could say that translation is my “solid and unshakable.” My first step to a career in literary translation overlapped precisely with my autism diagnosis aged twenty-eight. Repeated failed forays out of the isolation of academia into the “ordinary”—later, I would come to realize, ableist—world of work left both my mind and body in pieces. I had begun to think I would never be able to hold down a job at all, and mine is far from an isolated case, with 2021 statistics showing that only 29% of autistic people in the UK are in paid employment[1]. It was this inability to cope, with what others seemed to handle as if it was nothing, that eventually led me to read more and more about how entrenched gender bias in research had allowed generations of women on the spectrum to “slip under the radar.” At the same time, a colleague at the Korean Cultural Centre in London told me about the Literature Translation Institute of Korea’s scholarship program, and the prospect of a career translating, however precarious, felt like a light at the end of the tunnel.

For me, autism and translation thus exist co-dependently. It is my autism that led me to translate, and it is my autism that keeps me there. It is autism that, I believe, makes me an excellent linguist and translator—that same principle of “seeing everything, all at once” is what underlies my intense attention to detail, and the heightened pattern-seeking so common in autistic people is behind my fascination for linguistic and grammatical rules. Translation allows me to work according to my own routine and schedule. It allows me to work from home, where I can focus solely on the translation itself—deconstructing and manipulating the source text, remolding it into something new and precise—for hours on end, without having to interact with anyone at all. Yet, it is also with autism that come extra barriers to accessing a field already highly inaccessible. A field that relies heavily on connections and networking (an unappealing prospect for most, a destabilizing process for many autistic people), with little to no structure (the structured and practical guidance and support I received from translator Anton Hur as part of the UK National Centre for Writing Emerging Translator Mentorship program was, in no exaggerated terms, the sole reason I have been able to make a career out of literary translation).

We talk about better pay and working conditions for translators, as well as better access to enter the field, but these conversations become even more urgent for autistic people—and for other D/deaf, disabled, chronically ill, mentally ill, and/or neurodivergent people alike—for whom translation is a lifeline. In a sense, translation is not a career “choice” for me. Until the “typical” workplace undoes its deep-rooted ableist ways, I do not have the option of reverting to another career path, if this one doesn’t work out. This is one of the motivations underlying my role as part of the UK Society of Authors Translators Association Committee, and is also why this Massachusetts Review spotlight issue highlighting D/deaf, disabled, chronically ill, mentally ill, and/or neurodivergent artists—both its existence and being accepted to be a part of it—means so much. I long for a literary translation that is more open and transparent, with clearer systems and guidelines, where we move away from connections and networking, towards authentic community. I long for more people like me to be able to find, in languages and translation, something solid and unshakable of their own.

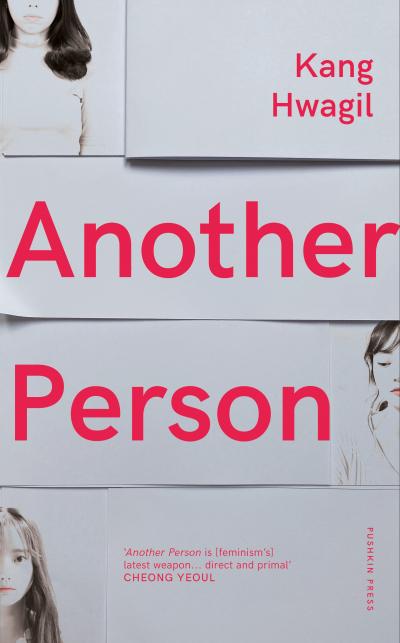

CLARE RICHARDS is a neurodivergent literary translator based in London. She has a particular interest in feminist fiction, and her upcoming publications include Kang Hwagil’s gothic thriller Another Person (Pushkin Press) and Park Min-jung’s short story "Like a Barbie" (Strangers Press). In 2022 Clare founded the D/deaf, Disabled and Neurodivergent Translators Network, and she also leads the UK Society of Authors Translators Association Committee Accessibility Working Group. Find her on Twitter @clarehannahmary and at clarerichards.crd.co.