10 Questions for Torsa Ghosal

- By Edward Clifford

Photo Credit: Jill Frank

Photo Credit: Jill Frank

Ma speaks with her eyes focused on some faint mark on the table's oilcloth. Hasnahena or Pāẏarā listens to the history of her naming again, after a long time. She has known it since her childhood. But, somehow, it is as though a festival celebrating her inconsequential human birth is still going on in this house.

—from "an Artist's Ego," by Shagufta Sharmeen Tania, translated by Torsa Ghosal, Volum 63, Issue 3 (Fall 2022)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

Growing up in the multilingual culture of India, I feel like I have been translating bits and pieces of literature pretty much all my life. I remember translating lines of Bengali poetry for Hindi-speaking friends on my school bus when I was in the eleventh standard. In college, a friend asked me to write the English subtitles for his documentary film that featured Bengali narration and speech. That, too, was an experience in translation. I have always written fiction and poetry in English, but my subjects and characters are located in contexts that would require them to speak in Bengali and Hindi, among other languages. So, my own writings are, to use Rebecca Walkowitz’s expression, “born translated.”

But I started thinking about literary translation more systematically during graduate school. I had to study a foreign language as part of my doctoral coursework, and I chose French. One of the requirements was to translate a piece of theory from French to English. I translated a dense essay on narrative theory and actually enjoyed the experience. Translating felt like a form of close, attentive reading. I then decided to work with Bengali literature in a similar way on my own time. I turned to excerpts from the collected personal writings of Binodini Dasi, a nineteenth century Bengali theater actor. I was interested in Binodini as a transgressive historical figure, and I had gotten hold of a copy of her writings in Bengali edited by Debjit Bandyopadhyay. Translating segments of the text allowed me to engage with Binodini Dasi’s thoughts and experiences in a more intimate way. I knew that Rimli Bhattacharya had translated Binodini Dasi’s writings and published them. But I was not thinking of publishing myself, and so, not worrying about the audience of my translation at all.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

Writers who have left a deep impression on me include Jibanananda Das, Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay, Virginia Woolf, Attia Hosain, Toni Morrison, Arundhati Roy, Anne Carson, and Tsitsi Dangarembga, among others. I cannot pinpoint if and how they influence my writing though. Anne Carson is a writer-translator who awes me with her use of language—Nox and Autobiography of Red are books I can read over and over. The trajectory of Carson’s translation career also intrigues me—she produced more traditional translations of plays earlier in her career and now she produces the kind of translation that is difficult to describe! They are witty, precise, idiosyncratic but deep readings of texts. I am stunned by whatever glimpse I get of her mind.

What other professions have you worked in?

I work as a professor of literature and creative writing at California State University, Sacramento, at present, along with working as a writer-translator. I also did a bit of freelance journalism while in college. I have never strayed very far from writing. My only work that did not involve writing was the couple of days I worked as an ad filmmaker’s assistant.

What did you want to be when you were young?

I wanted to be a physicist for a long time, then a computer scientist. I was drawn to the way physics explains our most fundamental experiences, especially phenomena involving light and energy. It felt neat, logical, and beautiful to me. My love for physics was supplanted by my interest in computer science when I learned coding. I learned to appreciate algorithms as structures of thought. Looking back, I think all along I had been very interested in the relationship of observable phenomena (whether real or simulated) with the abstract schema we use to make sense of them.

What drew you to write a translation of this piece in particular?

I was introduced to the author Shagufta Sharmeen Tania at a literary gathering for Bangladeshi and Bengali-speaking writers organized by an acquaintance. I heard her read a story at the gathering. It had vivid descriptions and while she was reading it, I kept wondering, how will all these sensory and local details culminate into something cohesive? But they did at the end. Afterward, the author and I corresponded, and when I read “Shilper Borai,” the original Bangla story that became “An Artist’s Ego,” I once again felt a sense of admiration for how Shagufta crafts complex narratives that comment on our social world out of vivid descriptions.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

West Bengal—the state in India where I was raised—influences my writing and imagination. It is also the setting for a host of my fictions. Seasons in Bengal, Bangla dialects, Bengali literature, the state’s notorious work and bandh cultures, its intricate religious and political history, particularly how Leftist ideas and texts entered people’s consciousness while the society also clung on to caste and class hierarchies, all these influence what I write. I have also been interested in the eclectic communities of people living in West Bengal whom the ethnic Bengalis like to call ‘non-Bengali’—the prejudices reflected in such labeling.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

I usually avoid listening to music while writing and editing because for me writing means working with the rhythms of language, sounds of words, and any external form of music would interfere with that. But, if my narrative mentions or describes a genre of music, I will listen to it while writing. For instance, my novella Open Couplets had two distinct sonic worlds: One was modeled after Kumartuli, a neighborhood in Calcutta, where clay idols are made. The other was associated with old Delhi and Lucknow–the characters in this world were interested in ghazals. I would listen to ghazals while writing those sections—I recall listening to Iqbal Bano’s rendition of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s poem "Dasht-e-Tanhai" on repeat. At present, I am working on a novel where characters engage with Ramprasadi devotional songs, and songs of Lalon Fakir, among other mystic poets. So, I sometimes listen to those songs before I start writing for the day to imbibe their texture. I have also translated some of those songs to include as text in my novel.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Dance. I trained in Kathak for many years, and much of my aesthetic attachments and affinities even as a writer can be traced to the features of the dance form.

What are you working on currently?

I am currently working on a novel about love and faith.

What are you reading right now?

I have just begun reading Sheela Tomy’s Valli, translated from Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil.

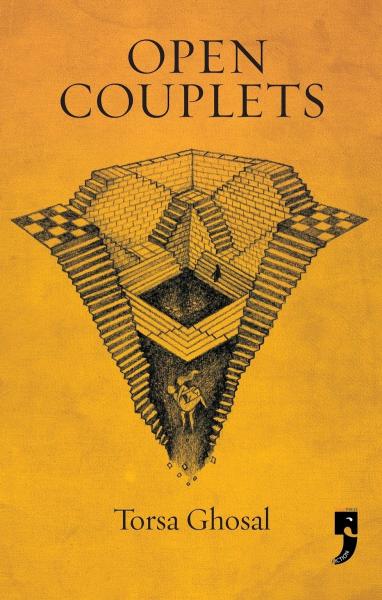

TORSA GHOSAL is the author of a book of literary criticism, Out of Mind (Ohio State University Press), and an experimental novella, Open Couplets (Yoda Press, India). Her fiction and essays have appeared in Necessary Fiction, Public Seminar, Literary Hub, Catapult, Michigan Quarterly Review Online, and elsewhere. She is an assistant professor of English at California State University, Sacramento.