Climate Nihilism (and Charles Baudelaire)

- By Maurizio Ferraris

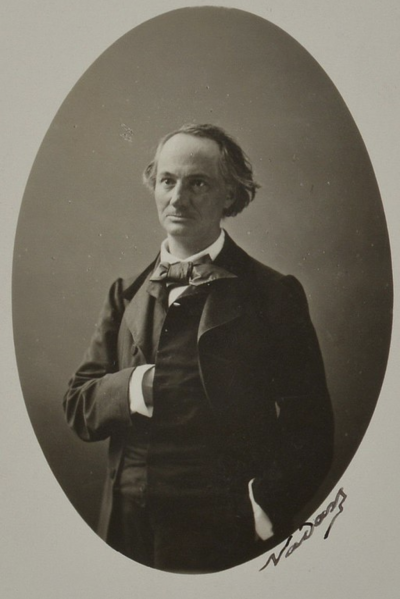

(Photo of Charles Baudelaire: Nadar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

"A theory of true civilization.

It rests not in gas, nor in steam, nor in table-turning.

It rests in the diminution of the traces of original sin."

The table-turning ("tables tournantes") was that of spiritualist seances, and the apothegm is Charles Baudelaire’s, from My Heart Laid Bare (1897, translation by Rainer J. Hanshe, 2017). What Baudelaire intends here is a denunciation of tekhnē and the Promethean arrogance of his age, with its “zoocratic and industrial philosophers,” obsessed by the “obscure beacon” of progress, as he wrote some years earlier, when disparaging the solemn rites celebrating progress at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Such opinions, a countercurrent in Baudelaire’s times, are now mainstream, part and parcel of that collective consciousness in which the dream of progress was transformed into the nightmare of globalization and the climate crisis. In an interview with Annalisa Cuzzocrea, Jonathan Safran Foer has said that “we are in a post-apocalyptic movie,” and Amitav Ghosh, interviewed by Alberto Simoni, added that “Nothing of what we could do to save the planet has a hope of actually being achieved.” Despite how understandable their worries may be, I hope and believe that their statements and predictions are wrong. Otherwise, the most reasonable behavior would be Bolsonaro’s: deforest the Amazon and enjoy humankind’s last days.

Greta Thunberg, Jonathan Safran Foer, Amitav Ghosh, just like the rest of us (Trump included), are all experiencing global warming and its consequences, all witnessing the war in Ukraine, and all (except Trump, who foresees a real estate benefit, given an increasing number of houses with an ocean view) formulate a unanimous decree: in respect to the political and climatic crisis, global responsibility is required and must be acted on, otherwise the Planet is finished. As for the end of the Planet, just to reassure everyone: it will continue to exist for millions of years in its verdant luxuriance of lifeforms, except without us, at least if we continue to move forward at the same rate. I believe this fact already gives some comfort to the animal-rights activists. As for the end of Humankind, to maintain that our fate is sealed (and it is! let’s not forget it! but not immediately) is equivalent to saying that, at this point, only a god can save us. And that, whether intended or not, is a nihilistic attitude that blocks us from taking on any sort of responsibility.

It’s fairly well known what nihilism consists of: the idea that all possible values amount to nothing and that humankind is destined for catastrophe. Not everyone (i.e., most of humankind) who is convinced that we are destined for catastrophe would admit to being a nihilist, but only because they don’t think it through. They don’t consider, for example, that proposing negative growth—which can only be infelicitous—as a remedy for the ecological crisis, or nothing whatsoever as remedy for the economic crisis, and again nothing whatsoever as remedy to the political crisis (or universal or unilateral disarmament, or universal love, or whatever) is nihilism. In short, it’s possible to have a heart replete with good intentions and still be more nihilist than a hero in Dostoevsky.

Nihilism is thinking that humankind has gone down the road to decadence, for who knows how long, and that it will soon arrive at the end of the line. Here already, if we care to pursue it, is a good question: when exactly did all that begin? The difficulty in assigning chronological limits to the Anthropocene—some would place its origins in 1964, with the discovery of residual radioactivity in corn pollen, others with the diffusion of agriculture, ten thousand years ago, and still others when fire was first controlled—ought to suggest that the Anthropocene is anything but the manifestation of the growing dominion of humankind over the environment, which itself has been resoundingly disproved (and not confermed, as has been erroneously asserted) by ecological disasters.

Nihilism is not wanting to admit that if, in July of 2022, the front pages of newspapers are dedicated to the deaths of hikers over melting glaciers and to the residents of a Ukrainian condominium targeted by a Russian missile, it is because these tragedies haven’t been obscured by the events of July 1945 (when in New Mexico the first atomic bomb exploded, and a few weeks later between one hundred and fifty and two hundred and twenty thousand Japanese civilians served as human guinea pigs), or by those of July 1916, when the Battle of the Somme began, which in a few months carried off three hundred thousand dead, along with more than a million wounded, or those of July 1520, when Hernán Cortés destroyed the vast capital of the Aztecs and launched a genocide that in just a few years vigesimated (i.e., decimated doubly) the population of México: from eighty million to four.

Nihilism is not taking stock of the fact that, as a whole, humankind has never had such a high standard of living and it has never been so numerous, and that precisely these numbers are causing the environmental catastrophe. Because without a doubt if today we had the technological and scientific instruments of the preindustrial world, Europe would have nonetheless been deforested (the problem was raging during the eighteenth century, and then the introduction of coal, rather than wood, as a source of alternative energy was an answer to ecological concerns), but we would be many fewer in number. Our life would be shorter and more full of misery, the rate of infant mortality sky-high, and physical labor would shape the lives of the majority of the population. In exchange, some people might conclude, nature would have kept its strength, after having suffered violence at the hands of humans. But those same people would be denying the evidence, because nature has never had a more healthy and robust constitution than it does today: just ask the viruses and bacteria, ask the mosquitos and rats, ask Charon and Katrina.

Today the absolute threat and concern is not safeguarding nature (which doesn’t require our help), but instead the power of nature. This concern sits in place of starvation, of that scarcity of resources which up until yesterday had been the naked ape’s greatest torment. And here two roads diverge. The first, the easy way out, consists of fulminating against the coming catastrophe, almost as if we hadn’t been aware of it already. The second and more difficult consists of finding alternate means of development that will permit us to balance out relations with the natural world, which has never been more inhospitable for humans, who are increasingly numerous and demanding—for goods as well as aid—and thus increasingly needy and vulnerable.

To our good fortune, we do have the knowledge and know-how, the necessary science and technology. And given that scientists are not some gang without scruples, driven by ambition (as certain respected critics proclaim), and that we ourselves are not slaves to technology (as other respected critics proclaim), since we are the masters, there is no shortage of ways to utilize science and technology in this sense. This isn’t a premonition, it’s a statement of fact. In this very moment millions of women and men of good will are working in that direction, and not only because we’re all in the same boat, but also because economic self-interest drives us toward sustainability. It’s difficult to sell stoves in an overheated world, and pointless to discover vaccines for a depopulated planet.

And so, Baudelaire was more reasonable than he assumed in uttering his reactionary boutade: real progress does consist of the diminution of the traces of original sin. In other words, humans are not perfect and virtuous beings corrupted by technology and society (as is proclaimed by utopians always prepared to curse the cynical, swindling fate that kept us from winning a lottery where we never bought a ticket), we are instead radically imperfect and defective beings, and thus in need of remedies that can only come from technology—that supplement with which, from the very start, we have strived, with relative success, to correct our shortcomings. And so real progress, diminishing the original sin, actually does run straight through gas, and steam, as well as their contemporary and more compatible successors (if we really do manage nuclear fusion, many of our problems will be resolved). On the other hand, when it comes to those Ouiji boards, as in the times of Baudelaire, I would urge more caution, though I suspect that today talk shows have taken their place. And even this, despite everything, is a form of progress. When it comes to knowing the problems we presently face, even the most apocalyptic of commentators has a better nose than Cleopatra.

Translated by Jim Hicks

Maurizio Ferraris is Professor of Philosophy in the Department of Literature and Philosophy at the Università di Torino, where he runs the LabOnt (Laboratory for Ontology). Recent works in Italian include Il denaro e i suoi inganni, with John R. Searle (Money and Its Tricks, 2018) and L'imbecillità è una cosa seria (Idiocy Is a Serious Problem, 2016); his publications translated in English include Manifesto of New Realism (2012, 2014) and History of Hermeneutics (1988, 1996).